Abstract

Background

Whiplash injuries are among the leading injuries related to car crashes and it is important to determine the prognostic factors that predict the outcome of patients with these injuries. This meta-review aims to identify factors that are associated with outcome after acute whiplash injury.

Materials and methods

A systematic search for all systematic reviews on outcome prediction of acute whiplash injury was conducted across several electronic databases. The search was limited to publications in English, and there were no geographical or time of publication restrictions. Quality appraisal was conducted with A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews.

Results

The initial search yielded 207 abstracts; of these, 195 were subsequently excluded by topic or method. Twelve systematic reviews with moderate quality were subsequently included in the analysis. Post-injury pain and disability, whiplash grades, cold hyperalgesia, post-injury anxiety, catastrophizing, compensation and legal factors, and early healthcare use were associated with continuation of pain and disability in patients with whiplash injury. Post-injury magnetic resonance imaging or radiographic findings, motor dysfunctions, or factors related to the collision were not associated with continuation of pain and disability in patients with whiplash injury. Evidence on demographic and three psychological factors and prior pain was conflicting, and there is a shortage of evidence related to the significance of genetic factors.

Conclusions

This meta-review suggests an association between initial pain and anxiety and the outcome of acute whiplash injury, and less evidence for an association with physical factors.

Level of evidence

Level 1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whiplash injury, or whiplash-associated disorder, can be defined as a collection of neck-related symptoms following a car accident [1] and is among the leading car crash-related injuries with respect to burden on patients, the healthcare system and insurance organisations. The incidence of whiplash injury has been increasing during the past decades [2], ranging from 16 to 200 per 100,000 population, and varying by geographical location [3]. In addition, patterns of crashes causing whiplash injury are changing, now including minor accidents of any type [4]. The increasing incidence may also be due to the rise in traffic density, and changes in societal and litigation factors [5]. It is estimated that 50 % of patients with acute whiplash injury develop long-term disability [6].

While various factors are considered to be related to the incidence and chronicity of acute whiplash injury, it is important to distinguish between risk factors for acute whiplash and prognostic factors for a poor outcome and chronicity in people who have sustained an acute whiplash injury (Fig. 1) [7]. Walton et al. have undertaken an overview of systematic reviews on prognostic factors in neck pain and have suggested that baseline neck pain intensity and disability are strongly associated with outcome, while trauma-related parameters have no effect on outcome [8]. Nevertheless, Walton et al. suggested the need for further work in this area. Considering the availability of more recent systematic reviews on the topic, we have undertaken a more focused systematic meta-review on the prognostic factors of outcome after acute whiplash injury, which aimed to answer the following questions: what is the quality of currently available systematic reviews on the prediction of outcome after acute whiplash injury; and which factors predict outcome after acute whiplash injury?

Materials and methods

As our preliminary search found several relevant systematic reviews, it was deemed feasible to undertake a meta-review [9]. A meta-review is a systematic overview of reviews, in which all available systematic reviews are included and rigorous appraisal of each included systematic review is undertaken [9]. Since each paper included in this study is a systematic review that has appraised a number of studies, this study has the opportunity to present a comprehensive and reliable picture of the field. The PRISMA statement guided the approach [10] (S1 PRISMA Checklist).

To identify the relevant papers, the medical subject heading (MeSH) of ‘whiplash’ and an extensive list of MeSH subheadings and a combination of relevant phrases were used (S2 Table 5). The lists of MeSH subheadings varied according to differences in the various databases. However, to ensure the sample would be a comprehensive collection of relevant systematic reviews, an attempt was made to over-include MeSH subheadings (i.e., subheadings that were not directly related to prognostic factors were also included). The electronic databases searched were: PubMed, Medline, Embase, Cochrane library, CINAHL and PsycINFO. The search was limited to publications in English, but was not limited by date of publication or geographical location. Non-systematic reviews, opinions, books, book chapters, discussions and letters were excluded. Other meta-reviews were cited and compared with this study, but not included in data analysis.

During the screening phase, we included systematic reviews if they directly reported results on whiplash and we excluded reviews if they combined data related to whiplash with other musculoskeletal injuries. We also included only systematic reviews that explored prognostic factors, as outlined in the background section, and excluded papers that explored other issues such as the determinants of incidence of acute whiplash injury. Studies were considered as systematic reviews if they clearly introduced the searched databases and key terms, and reported the number of identified papers. Papers were first screened for their topic and methodology based on their titles and abstracts. The full texts of selected papers were then obtained, and evaluated independently by two reviewers (PS and EA). The results of the two reviewers were compared, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

After including a number of systematic reviews based on their topic and methodology, the quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed using A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) [11].

Data analysis involved producing a list of prognostic factors for each systematic review, and then the conclusions obtained from each systematic review were recorded for each factor.

The conclusion of each review for each identified prognostic factor was determined and recorded using the following classification: (1) associated: when the systematic review found adequate evidence to conclude that a prognostic factor was associated with the outcome of acute whiplash injury; (2) non-associated: when the systematic review found adequate evidence to conclude that a prognostic factor was not associated with the outcome of whiplash; (3) lack of evidence: when the systemic review reported being unable to identify adequate evidence regarding a prognostic factor; and (4) controversial: when the systematic review found controversial or conflicting evidence regarding a prognostic factor.

A prognostic factor was allocated to one of the first three categories (associated, non-associated, or lack of evidence) whenever the majority of the systematic reviews that analysed each factor agreed on the association or lack of association with the outcome, or if they referred to a lack of evidence. A prognostic factor was placed in the fourth category (controversial) if the majority of the systematic reviews referred to controversial evidence, or if we identified controversial conclusions in the systematic reviews.

A priori, the intent of the analysis was to indicate the overall direction of current evidence for each of the prognostic factors in a qualitative manner with no report on quantitative strength of effects.

Results

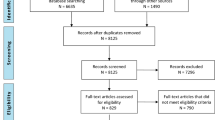

Initial searches in different databases yielded 365 articles, and the screening process for these articles is summarised in Fig. 2. Of the 365 articles found, 158 were duplicates, 105 items were excluded based on the evaluation of title and abstract and 90 papers were excluded after appraisal of their full text (S3 Table 6. Excluded studies). The remaining 12 papers (referenced in Table 1) were rated for quality using the AMSTAR tool as moderate quality (score 5–8) and their average score was 6.7 (out of 11, with the range of 6–8). They included systematic reviews focussing on whiplash injuries with no fractures or dislocations.

Prognostic factors

A broad range of prognostic factors was explored by the systematic reviews included. Analysis of the final 12 reviews indicated that four groups of factors were associated with the outcome of acute whiplash injury (Table 2), three groups of factors were identified as non-associated (Table 3), and the evidence was controversial or insufficient for five other factors (Table 4). Heterogeneity and variations in the systematic reviews included precluded quantitative analysis.

Associated factors

Factors associated with the prognosis for people with whiplash injury were (Table 2):

-

Post-injury pain and disability (i.e., pain and disability that whiplash patients experience after a car accident), whiplash grades, cold hyperalgesia

-

Post-injury anxiety

-

Catastrophizing

-

Compensation and legal factors

-

Early use of healthcare

The most consistent finding of the systematic reviews was the association of post-injury pain and disability with long-term pain and disability. Whether directly exploring this factor, or referring to whiplash grades and cold hyperalgesia, six different systematic reviews suggested the association [15, 17–19, 21, 23]. However, the association of other factors with the prognosis for patients with whiplash is not as strong, although the association of psychosocial factors with a whiplash prognosis is notable. Psychosocial factors are the combination of social factors, for example compensation and legal matters, with psychological factors, such as post-injury anxiety and catastrophizing. As indicated in Table 2, we identified two or three systematic reviews for each of the other factors; some of the available reviews were based on systematic reviews conducted more than 5 years ago, and there were two reviews that reported lack of evidence for some of these factors.

Non-associated factors

Factors identified as not being associated with the prognosis of whiplash were post-injury magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or radiological findings; motor dysfunctions; and collision factors (i.e., factors related to the car accident such as the direction of impact, the use of seatbelts or headrests, and the speed of the car at the time of impact [18]). As indicated in Table 3, the lack of association of collision factors with the prognosis of whiplash was confirmed based on four reviews, while we identified only one or two reviews covering each of the other two factors. It is notable that the list of non-associated factors is more related to ‘physical’ and biological items.

Controversial or insufficient evidence

Current evidence is conflicting for the association of demographic factors (gender, age and education), three psychological factors (coping behaviour, general psychological distress and depressive mood) and pre-accident pain with the prognosis of whiplash. A lack of evidence is reported for genetic factors.

Discussion

This meta-review, summarising the results of twelve systematic reviews, indicates that the outcome of patients with acute whiplash injury is associated with post-injury symptoms and some psychosocial factors, and not injury-related physical or mechanical factors. These findings are consistent with a previous meta-review that explored prognostic factors of neck pain in general [8]. To summarise and simplify the result of this meta-review, a ‘typical’ whiplash patient with a poor outcome (that is, prolonged pain and disability) can be depicted as having severe pain and anxiety, and is seeking or has sought legal advice and early healthcare use. The type of accident, findings on physical examination, or radiological investigations will not affect the prognosis. Thus, a patient suffering chronic pain and disability post-whiplash can potentially be involved in a minor car accident with no motor dysfunction or radiological abnormality. The association of some psychosocial factors with the chronicity of whiplash injury is in accordance with previous studies involving chronic pain patients, which indicate a similar association between psychosocial factors and the course of chronic pain in general [24], and other forms of chronic pain such as non-specific low back pain [25, 26].

It is also notable that current evidence is conflicting or lacking on factors such as demographic factors (age, gender and education), three psychological factors and pain prior to accident. It is notable that Walton et al. concluded in their meta-review, with moderate confidence, that age has no effect on the outcome of whiplash [8]. This contrasts with our analysis, which concluded controversial evidence based on an association reported by Cote et al. [23]. This lack of conclusiveness might be explained by differences in the methodologies of various studies, such as different sample frames (normal population, insurance population or hospital emergency departments) [13, 16, 23]. In addition, the effect of demographic factors is not usually direct, but is mediated by other factors [27]; therefore, future studies should consider the role of confounding factors, such as comorbid mental health problems, while exploring the association of demographic factors with the prognosis of whiplash injury.

All twelve papers included in this review emphasised the need for more rigorous evidence, and made suggestions for future work in this field. These included the need for further studies on some of the prognostic factors, the need to explore the causal effect of other factors, and studies assessing the possibility of using prognostic factors in the prevention or treatment of whiplash whenever possible, as discussed below.

Carroll et al. reported a lack of high-quality studies on the association of the following items with the prognosis of whiplash: occupation type, disc degeneration, cultural factors, pre-injury fitness or exercise, and pre-existing or new incidence of widespread body pain or fibromyalgia [6]. Cote et al. emphasised that, based on current evidence, it is not clear whether the course of whiplash differs in patients recruited from the general population compared to those recruited from emergency departments or primary care practice [23]. Spearing et al. could not find any studies that directly explored the role of receiving compensation payment on the prognosis of whiplash patients [16]. Finally, Williamson et al. reported a lack of high-quality evidence on the association of psychological factors and chronicity of acute whiplash injury [20]. These areas should be investigated in any future studies.

The association of a factor with the prognosis of whiplash does not necessarily reflect a causal relationship; such associated factors cannot therefore be necessarily used as a basis for the treatment or prevention of whiplash. More studies are necessary to investigate the potential role of prognostic factors on aetiology, prevention and treatment of whiplash. For example, although cold hyperalgesia is associated with pain and disability in whiplash patients, more studies are needed to investigate whether cold hyperalgesia can be considered as a cause of pain, or if there are other confounding factors [28]. Another example is related to the role of compensation, which is associated with poor health outcome [29, 30]; however, studies have yet to explore reverse causality, that is, the poor outcome being the cause of compensation-seeking [16, 31].

In addition, future studies should explore whether a patient’s outcome can be improved by removing a prognostic factor. For example, while whiplash patients who report back pain following a car accident are more likely to have a poor outcome, more studies are needed to determine if treating the back pain can improve the outcome of whiplash [15].

Considering the complexities that exist around the association of factors with outcome of a health condition such as acute whiplash injury, complete elaboration of such associations would be beyond the scope of a single study, and different phases of research might be needed to identify, confirm and understand prognostic associations [32]. It is also necessary that future studies employ rigorous methodology (such as using validated and objective measures) and reporting standards (including the use of magnitude of associations) [8, 15, 19, 33].

We did not identify any recent systematic reviews (within the past 5 years) that examined psychological factors, early healthcare use and motor dysfunctions. It would be helpful to undertake updated systematic reviews to explore the association of these factors with the prognosis of whiplash.

Our methodology had the benefit of relying on the best available evidence provided by the systematic reviews included, but this has limitations. More recent studies would not have been captured by the included reviews. In addition, by including all the prognostic factors explored by the systematic reviews, this meta-review maps the field and provides an overall picture, but in doing so, it necessarily reduces the depth of analysis for each individual factor.

In conclusion, this meta-review provides a comprehensive overview of the state of the high-level evidence available concerning the factors associated with the outcome of patients with whiplash injuries. The predictors of poor outcome after acute whiplash injury are early pain and some psychosocial factors, whereas physical factors are not associated with the outcome of acute whiplash.

References

Pearce J (1989) Whiplash injury: a reappraisal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 52(12):1329–1331

Galasko C, Murray P, Pitcher M, Chambers H, Mansfield S, Madden M et al (1993) Neck sprains after road traffic accidents: a modern epidemic. Injury 24(3):155–157

Pastakia K, Kumar S (2011) Acute whiplash associated disorders (WAD). Open Access Emerg Med 3:29–32

Malleson A (1994) Chronic whiplash syndrome. Psychosocial epidemic. Can Fam Phys 40:1906–1909

Livingston M (2000) Whiplash injury: why are we achieving so little? J R Soc Med 93(10):526–528

Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S et al (2008) Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine 33(4 Suppl):S83–S92

Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW, Wagner EH (1996) Clinical epidemiology: the essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Walton DM, Carroll LJ, Kasch H, Sterling M, Verhagen AP, Macdermid JC et al (2013) An overview of systematic reviews on prognostic factors in neck pain: results from the International Collaboration on Neck pain (ICON) project. Open Orthop J 7:494–505

Sarrami‐Foroushani P, Travaglia J, Debono D, Clay‐Williams R, Braithwaite J (2015) Scoping meta‐review: introducing a new methodology. Clin Transl Sci 8(1):77–81

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther 89(9):873–880

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C et al (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 7(1):10

Li Q, Shen H, Li M (2013) Magnetic resonance imaging signal changes of alar and transverse ligaments not correlated with whiplash-associated disorders: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Eur Spine J 22(1):14–20

Daenen L, Nijs J, Raadsen B, Roussel N, Cras P, Dankaerts W (2013) Cervical motor dysfunction and its predictive value for long-term recovery in patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med 45(2):113–122

Walton DM, Pretty J, Macdermid JC, Teasell RW (2009) Risk factors for persistent problems following whiplash injury: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 39(5):334–350

Walton DM, Macdermid JC, Giorgianni AA, Mascarenhas JC, West SC, Zammit CA (2013) Risk factors for persistent problems following acute whiplash injury: update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 43(2):31–43

Spearing NM, Connelly LB, Gargett S, Sterling M (2012) Does injury compensation lead to worse health after whiplash? A systematic review. Pain 153(6):1274–1282

Goldsmith R, Wright C, Bell SF, Rushton A (2012) Cold hyperalgesia as a prognostic factor in whiplash associated disorders: a systematic review. Man Ther 17(5):402–410

Carroll LJ, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Cassidy JD, Haldeman S et al (2008) Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine 33(4S):S83–S92

Kamper SJ, Rebbeck TJ, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M (2008) Course and prognostic factors of whiplash: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 138(3):617–629

Williamson E, Williams M, Gates S, Lamb SE (2008) A systematic literature review of psychological factors and the development of late whiplash syndrome. Pain 135(1–2):20–30

Williams M, Williamson E, Gates S, Lamb S, Cooke M (2007) A systematic literature review of physical prognostic factors for the development of Late Whiplash Syndrome. Spine 32(25):E764–E780

Scholten-Peeters GG, Verhagen AP, Bekkering GE, van der Windt DA, Barnsley L, Oostendorp RA et al (2003) Prognostic factors of whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Pain 104(1–2):303–322

Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Frank JW, Bombardier C (2001) A systematic review of the prognosis of acute whiplash and a new conceptual framework to synthesize the literature. Spine 26(19):E445–E458

Turk DC, Okifuji A (2002) Psychological factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J Consult Clin Psychol 70(3):678

Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP (2002) A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 27(5):E109–E120

Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Mayer TG (1995) The dominant role of psychosocial risk factors in the development of chronic low back pain disability. Spine 20(24):2702–2709

Christenfeld NJ, Sloan RP, Carroll D, Greenland S (2004) Risk factors, confounding, and the illusion of statistical control. Psychosom Med 66(6):868–875

Goldsmith R, Wright C, Bell SF, Rushton A (2012) Cold hyperalgesia as a prognostic factor in whiplash associated disorders: a systematic review. Man Ther 17(5):402–410

Cote P, Soklaridis S (2011) Does early management of whiplash-associated disorders assist or impede recovery? Spine 36(25S):S275–S279

Harris IA (2007) Personal injury compensation. ANZ J Surg 77(8):606–607

Spearing NM, Connelly LB, Gargett S, Sterling M (2012) Does injury compensation lead to worse health after whiplash?A systematic review. Pain 153(6):1274–1282

Hayden J, Cote P, Steenstra I, Bombardier C, Q-LW Group (2008) Identifying phases of investigation helps planning, appraising, and applying the results of explanatory prognosis studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61(6):552–560

Carroll LJ, Hurwitz EL, Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Carragee EJ, Nordin M et al (2008) Research priorities and methodological implications: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine 33(4 Suppl):S214–S220

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded by the Motor Accident Authority (MAA), New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors confirmed having no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarrami, P., Armstrong, E., Naylor, J.M. et al. Factors predicting outcome in whiplash injury: a systematic meta-review of prognostic factors. J Orthopaed Traumatol 18, 9–16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10195-016-0431-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10195-016-0431-x